Vaquita

Phocoena sinus

In addition to being the smallest member of the porpoise family, vaquita are the smallest of all known cetaceans, have the most restricted range, and are the most critically endangered of all cetaceans. Native to Mexico, their scientific name, Phocoena sinus means “porpoise of the gulf”. Vaquita is Spanish for “little cow”. Their other common names are Gulf of California harbor porpoise, cochito, and vaquita marina. They were not discovered or named until 1958 when three skulls were found on the beach. More than 40 years later little is known about their natural history, and they may become extinct before more is known. Current knowledge is based on sightings of live animals, observations of stranded or trapped animals, and necropsies.

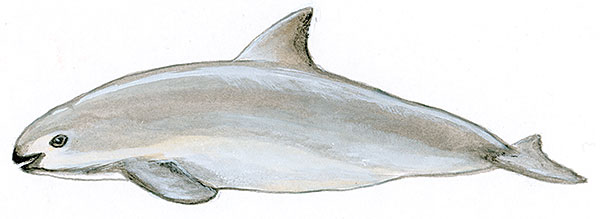

Artist's drawing of vaquita Credit: © Aquarium of the Pacific

SPECIES IN DETAIL

Vaquita

Phocoena sinus

CONSERVATION STATUS: Endangered - Protected

CLIMATE CHANGE: Not Applicable

At the Aquarium

Due to the space requirements for these intelligent and dynamic animals, we do not exhibit live cetaceans. This information is available for a reference.

Geographic Distribution

Restricted to northwestern corner of Gulf of California (Sea of Cortez) and, perhaps, the Colorado River Delta.

Habitat

Vaquita live in shallow lagoons no more than 25 km (16 mi) from shore where there is a strong tidal mix. Although they can survive in lagoons that are so shallow that their back protrudes above the surface of the water, they prefer water that is 10 to 28 m (33 to 92 ft) deep.

Physical Characteristics

Vaquita have the typical robust body shape of a porpoise with the middle of the body measuring about 68% of the body length. They have little or no beak with a slight protrusion of the upper jaw at the base of the melon. Their dorsal fin is upright with a straight vertical or slightly curved (falcate) rear margin and bumps and whitish spots on the leading edge. Their dorsal fin is relatively large when compared to that of other porpoise species.

They are dark gray on their upper body and halfway down their sides where the coloration fades to a lighter gray. The throat and belly are streaked with white. There is a dark stripe extending from the middle of the lower jaw to the front of the flippers. They have black eye and chin patches and black lips. Juveniles are darker than adults.

Size

Adults are 1.2-1.5 m (3.9-4.9 ft) long and weigh about 45 to 50 kg (99 to 110 lb). Females tend to be larger than males.

Diet

Examination of stomach contents of dead animals has shown that vaquitas are not picky about their diet, eating a variety of fish species (17 species found in one animal) that live near or on the gulf bottom. They also eat squid and crabs.

Reproduction

Little is known about vaquita reproduction but researchers believe it is probably similar to that of harbor porpoises. If that is true, then sexual maturity is reached at three to five years of age and the gestation period is probably about 11 months. Births occur in February-April, peaking in late March to early April. Newborn calves are 70-78 cm (31-38 in) long and weigh 7.5 kg (17 lb). The calf probably nurses for six to eight months.

Many scientists believe that vaquita will become extinct because the genetic pool is too small for effective reproduction

Behavior

Vaquita are shy, rather secretive animals. They have been observed singly, in pairs, and in groups of up to seven animals. They generally do not engage in acrobatics at the surface of the water, emerging from beneath the surface with a slow, forward-rolling movement that barely disturbs the water’s surface, taking a breath, and then quickly disappearing in a quiet dive.

These porpoises echolocate using a series of high frequency clicks.

Adaptation

The closest porpoise species to vaquita geographically is central California’s harbor porpoise which is 2500 km (1500 mi) distant, however, they are more closely related morphologically to Burmeister’s porpoise which occur from Peru southward, 5000 km (3000 mi) away. It is thought that vaquita evolved from an ancestral population of Burmeister’s porpoise that moved northward into the Gulf of California one million years ago.

Vaquitas are the only porpoise species adapted to living in warm water. Most porpoises inhabit water that is cooler than 20oC (68oF) whereas vaquita are able to tolerate water that fluctuates from 14oC (57oF) in the winter to 36oC (97oF) in the summer.

Longevity

These porpoises may live 20 years if they escape gillnets.

Conservation

Vaquita and totoaba (Totoaba macdonald), a large sea bass species, share habitat, the northern or upper area of the Gulf of California and that sharing of habitat is the major reason why vaquita may become extinct. Today both vaquita and totoaba are listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species and as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act and by the Mexican government. Additionally vaquita are protected under the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Commercial fisheries used gill nets to harvest totoaba and vaquita are very vulnerable to entanglement in such nets. Like all cetaceans vaquita do not have gills as fish do—they breathe air. Once entangles in a net, they cannot surface for air. While use of large mesh gill nets was banned, smaller nets still entangle vaquita as bycatch. Overfishing of totoaba resulted in ban on harvesting this species but illegal poaching continues. For almost five decades various measures have been instituted to save vaquia from extinction as shown in these chronological list but they have not halted the decline of this porpoise.

1930: Commercial fishing for totobaba using gill nets starts

1947: Harvest of totoaba peaks

1958: Vaquita observed in the upper Gulf of California

1972: U.S. protects vaquita under the Marine Mammal Protection Act

1975: Mexico bans commercial fishing for totoaba and lists the fish as endangered

1975: Mexico alao list vaquita as endangered

1976: U.S. lists totoaba as endangered following

1977: U.S. bans import of totoaba; however, it still appears in U.S. in markets in border states

1992: Mexico bans use of large mesh gill nets

1993: Mexico established the Upper Gulf of California and Colorado River Biosphere Reserve to provide protection for vaquita, totoaba, sea urtles, and other wildlife.

1996: Vaquita listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species

2008/2010: Vaquia population re-surveyed and listing as critically endangered continues both because of gill net mortality and estimated inability to recover in three generations

2010 Totoaba listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species

2015: 2015: The Mexican Government establishes atwo year ban on gillnets throughout the vaquita’s range following recommendations of (the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita ( CIRVA)).

The Future: Various international organizations and government agencies including the IUCN Cetacean Specialist Group, International Whaling Commission’s Small Cetacean Subcommittee, World Wildlife Fund, U.S.’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and several Mexican government agencies are involved in efforts to saving the vaquita. Time will tell whether vaquita, now considered the most vulnerable cetacean, survive.

Special Notes

The terms porpoise and dolphin are often used interchangeably in error. There are differences between the two cetaceans. Porpoises are smaller, more robust, have smaller more triangular dorsal fins, lack a prominent beak, and have spade instead of conical-shaped teeth. Most inhabit shallow, nearshore waters and rarely follow vessels as dolphin often do bowriding or surfing in the wake.

Vaquita and totoaba (Totoaba macdonaldi), a large sea bass species, share habitat, the northern or upper area of the Gulf of California and that sharing of habitat is the major reason why vaquita may become extinct. Today both vaquita and totoaba are listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species and as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act and by the Mexican government. Additionally vaquita are protected under the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act.

SPECIES IN DETAIL | Print full entry

Vaquita

Phocoena sinus

CONSERVATION STATUS: Endangered - Protected

CLIMATE CHANGE: Not Applicable

Due to the space requirements for these intelligent and dynamic animals, we do not exhibit live cetaceans. This information is available for a reference.

Restricted to northwestern corner of Gulf of California (Sea of Cortez) and, perhaps, the Colorado River Delta.

Vaquita live in shallow lagoons no more than 25 km (16 mi) from shore where there is a strong tidal mix. Although they can survive in lagoons that are so shallow that their back protrudes above the surface of the water, they prefer water that is 10 to 28 m (33 to 92 ft) deep.

Vaquita have the typical robust body shape of a porpoise with the middle of the body measuring about 68% of the body length. They have little or no beak with a slight protrusion of the upper jaw at the base of the melon. Their dorsal fin is upright with a straight vertical or slightly curved (falcate) rear margin and bumps and whitish spots on the leading edge. Their dorsal fin is relatively large when compared to that of other porpoise species.

They are dark gray on their upper body and halfway down their sides where the coloration fades to a lighter gray. The throat and belly are streaked with white. There is a dark stripe extending from the middle of the lower jaw to the front of the flippers. They have black eye and chin patches and black lips. Juveniles are darker than adults.

Adults are 1.2-1.5 m (3.9-4.9 ft) long and weigh about 45 to 50 kg (99 to 110 lb). Females tend to be larger than males.

Examination of stomach contents of dead animals has shown that vaquitas are not picky about their diet, eating a variety of fish species (17 species found in one animal) that live near or on the gulf bottom. They also eat squid and crabs.

Little is known about vaquita reproduction but researchers believe it is probably similar to that of harbor porpoises. If that is true, then sexual maturity is reached at three to five years of age and the gestation period is probably about 11 months. Births occur in February-April, peaking in late March to early April. Newborn calves are 70-78 cm (31-38 in) long and weigh 7.5 kg (17 lb). The calf probably nurses for six to eight months.

Many scientists believe that vaquita will become extinct because the genetic pool is too small for effective reproduction

Vaquita are shy, rather secretive animals. They have been observed singly, in pairs, and in groups of up to seven animals. They generally do not engage in acrobatics at the surface of the water, emerging from beneath the surface with a slow, forward-rolling movement that barely disturbs the water’s surface, taking a breath, and then quickly disappearing in a quiet dive.

These porpoises echolocate using a series of high frequency clicks.

The closest porpoise species to vaquita geographically is central California’s harbor porpoise which is 2500 km (1500 mi) distant, however, they are more closely related morphologically to Burmeister’s porpoise which occur from Peru southward, 5000 km (3000 mi) away. It is thought that vaquita evolved from an ancestral population of Burmeister’s porpoise that moved northward into the Gulf of California one million years ago.

Vaquitas are the only porpoise species adapted to living in warm water. Most porpoises inhabit water that is cooler than 20oC (68oF) whereas vaquita are able to tolerate water that fluctuates from 14oC (57oF) in the winter to 36oC (97oF) in the summer.

These porpoises may live 20 years if they escape gillnets.

Vaquita and totoaba (Totoaba macdonald), a large sea bass species, share habitat, the northern or upper area of the Gulf of California and that sharing of habitat is the major reason why vaquita may become extinct. Today both vaquita and totoaba are listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species and as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act and by the Mexican government. Additionally vaquita are protected under the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Commercial fisheries used gill nets to harvest totoaba and vaquita are very vulnerable to entanglement in such nets. Like all cetaceans vaquita do not have gills as fish do—they breathe air. Once entangles in a net, they cannot surface for air. While use of large mesh gill nets was banned, smaller nets still entangle vaquita as bycatch. Overfishing of totoaba resulted in ban on harvesting this species but illegal poaching continues. For almost five decades various measures have been instituted to save vaquia from extinction as shown in these chronological list but they have not halted the decline of this porpoise.

1930: Commercial fishing for totobaba using gill nets starts

1947: Harvest of totoaba peaks

1958: Vaquita observed in the upper Gulf of California

1972: U.S. protects vaquita under the Marine Mammal Protection Act

1975: Mexico bans commercial fishing for totoaba and lists the fish as endangered

1975: Mexico alao list vaquita as endangered

1976: U.S. lists totoaba as endangered following

1977: U.S. bans import of totoaba; however, it still appears in U.S. in markets in border states

1992: Mexico bans use of large mesh gill nets

1993: Mexico established the Upper Gulf of California and Colorado River Biosphere Reserve to provide protection for vaquita, totoaba, sea urtles, and other wildlife.

1996: Vaquita listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species

2008/2010: Vaquia population re-surveyed and listing as critically endangered continues both because of gill net mortality and estimated inability to recover in three generations

2010 Totoaba listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species

2015: 2015: The Mexican Government establishes atwo year ban on gillnets throughout the vaquita’s range following recommendations of (the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita ( CIRVA)).

The Future: Various international organizations and government agencies including the IUCN Cetacean Specialist Group, International Whaling Commission’s Small Cetacean Subcommittee, World Wildlife Fund, U.S.’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and several Mexican government agencies are involved in efforts to saving the vaquita. Time will tell whether vaquita, now considered the most vulnerable cetacean, survive.

The terms porpoise and dolphin are often used interchangeably in error. There are differences between the two cetaceans. Porpoises are smaller, more robust, have smaller more triangular dorsal fins, lack a prominent beak, and have spade instead of conical-shaped teeth. Most inhabit shallow, nearshore waters and rarely follow vessels as dolphin often do bowriding or surfing in the wake.

Vaquita and totoaba (Totoaba macdonaldi), a large sea bass species, share habitat, the northern or upper area of the Gulf of California and that sharing of habitat is the major reason why vaquita may become extinct. Today both vaquita and totoaba are listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species and as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act and by the Mexican government. Additionally vaquita are protected under the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act.