Emperor Penguin

Aptenodytes forsteri

Emperor Penguins can dive to an ocean depth of 600 feet (182 meters), the deepest limit with enough light for phytoplankton to grow.

Emperor Penguins are not only the largest of the world’s penguins, they are the only penguins to lay eggs and raise chicks almost exclusively on pack ice in the harsh and hostile Antarctic winter where air temperatures can be as low as -40oC (-40oF), wind speeds can reach 144 kilometers per hour (80 mph). Blizzards can bring winds that are over 200 kilometers per hour (124 mph), and water temperatures can be a frigid -18oC (28oF). They forage exclusively in Antarctica’s cold waters. Dedicated parents, they travel from 50 to 120 km (31-75 miles) from inland rookeries to open waters to forage, and then walk back to the colony to feed their chicks.

One if the three penguins in the the Aquarium's penguin size comparison model display, the four-foot Emperor Penguin model has become a very popular photo opportunity. Credit: Aquarium of Pacific. C. Fisher

Colony of Emperor Penguin adults and chicks near the U.S. McMurdo Station on Ross Island, Antarctica Credit: Courtesy of Giuseppe Zibordi & Michael Van Woert, NOAA NESDIS, ORA

SPECIES IN DETAIL

Emperor Penguin

Aptenodytes forsteri

CONSERVATION STATUS: Safe for Now

CLIMATE CHANGE: Vulnerable

At the Aquarium

The Aquarium’s Emperor Penguin is one of three models in the June Keyes Penguin Habitat that illustrate the wide size range among the world’s penguins. The Emperor is the largest of the three penguin models, (Emperor, Magellanic, and Little Blue), and this four foot model has become a very popular photographic opportunity.

Geographic Distribution

Breeding: The Emperor Penguin breeds on pack ice surrounding the Antarctic continent, Antarctica Peninsula, and islands off the peninsula up to 18 km (11.2 mi) offshore. Land colonies have been seen at Dion Island on the Antarctic Peninsula and at Taylor in the Australian Antarctic Territory. Vagrants have been seen at the South Shetland Islands, Tierra del Fuego, the Falklands, South Sandwich Islands, Kerguelen Island, Heard Island, and New Zealand.

Non-breeding: Little is known about the migration patterns of Emperor Penguins, but adults seem to stay close to permanent ice while juveniles migrate as far north as the polar front (zone of transition between polar and subtropical and tropical air masses).

Habitat

During breeding season, colonies are usually found inhabiting the stable fast ice attached to the ice shelves and coastlines surrounding the Antarctic continent. The most successful colonies are those that are established on stable pack ice in bays between islands that are somewhat sheltered from the fierce and harsh Antarctic winter winds by icebergs and ice cliffs. From January to March, the austral summer, they inhabit Southern Ocean waters.

Physical Characteristics

Emperor Penguins, the largest of the world’s penguins, have a large head; short, thick neck; and a wedge-shaped tail. Their upper bill is black but the coloration of the lower bill varies and can be pink, orange, or lilac. Adults have the basic black and white coloration of most penguins, but they also have some distinguishing coloration in the form of a pale yellow upper breast connecting to bright yellow ear patches. The head, neck, chin, and throat are black with some white areas on the sides of the head and neck. The back is a blue-gray-black color, and the belly and undersides of the flippers are mostly white. Between November and February, the dark plumage fades from black to a brownish color. Unique to Emperors, their feet and the base of their bill are feathered, as are the outer side of their flippers. Juveniles lack the yellow plumage of adults; their ear patches, chin, and throat are white; and they have an all-black bill. Chicks have a black and white face and a body covered with silver-gray down.

Size

Standing height: 0.9-1.2 m (3-4 ft)

Length, the measurement from tip of the beak to end of the tail): 1.1-1.3 m (3.7-4.3 ft) Weight: 22 to 45 kg (49-99 lb)

The weight of these penguins varies seasonally. They are heaviest at the start of the breeding season after spending several months foraging, and at the end of the breeding season after their pre-molt foraging. Both males and females lose weight during the breeding season when they are caring for eggs and feeding chicks.

Diet

Adult Emperor Penguins consume 2-5 kg (4.4-11 lb) of food per day except at the start of the breeding season or when they are building up their body mass in preparation for molting. Then they eat as much as six kilograms (thirteen pounds) per day.

Although the diet of Emperor Penguins varies by location and may include fish, krill, or squid, the most important food source is fish, especially Antarctic silversides. Krill and glacial and hooked squid supplement their fish diet. Foraging, which is usually done in flocks, occurs in ice free ocean waters and in tidal water in cracks in the pack ice. While some prey is captured by surface feeding, the usual method is by long, deep, pursuit diving. Emperors are very efficient divers. Shallow dives take two to four minutes while deeper dives can last as long as 12 minutes. Average dive depths are 18 to 21 m (60 to 70 ft). The tongue has rear-facing barbs to prevent prey from escaping when caught.

Reproduction

<

figure>

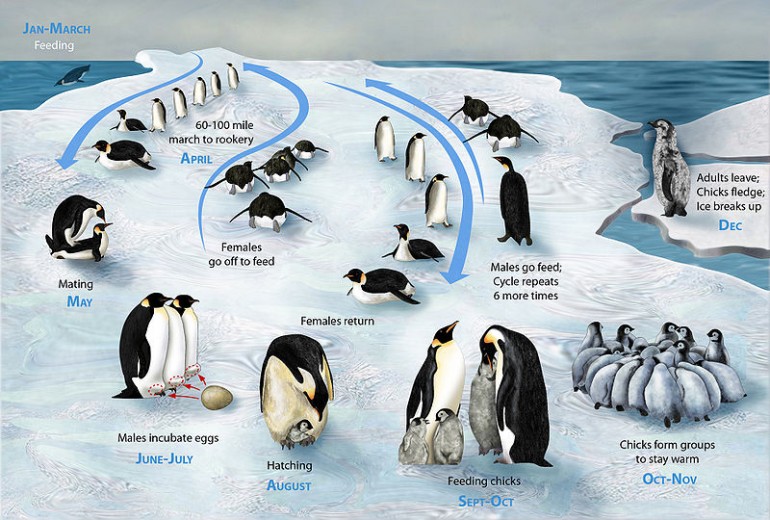

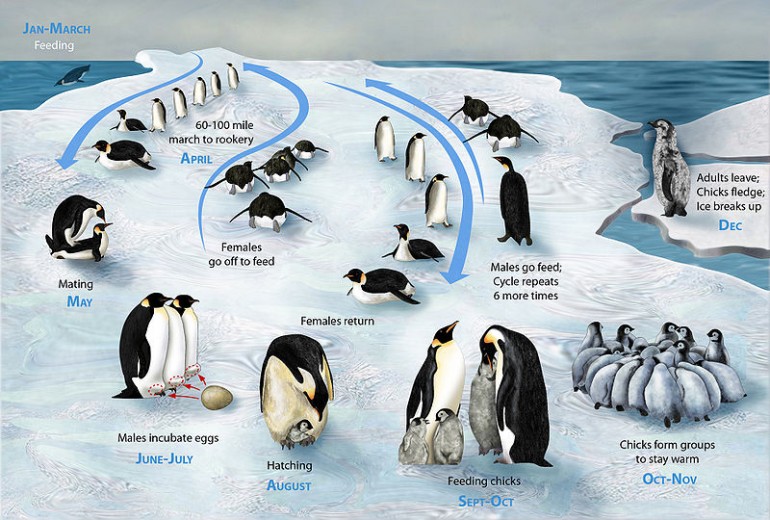

Emperor Penguins become sexually mature at three years of age; however, they usually do not start breeding until four to six years old. In late April/early May at the start of the austral winter, the march of the penguins begins when the birds exit the frigid ocean water and climb onto the pack ice. They then waddle and toboggan on their bellies at a speed of one km/hr (1.6 mph) to the breeding site, usually where they were born. There are about 46 known colonies of Emperor Penguins and the distance of the rookeries are 96 to 160 km (60-100 mi) inland.

Unlike many other penguins that usually mate for life, Emperors choose a new mate each year. They are faithful to that mate for the breeding season only. The male uses posturing and vocalization to attract a female. When he is successful, the pair waddles around the colony together. Then, just before mating actually occurs, each bows to the other by pointing its bill close to the ground.

The female lays a single egg in May or early June which she transfers to the male. Emperors do not build a nest and for the next 60 to 64 days, the male balances the egg on top of his feet, keeping it warm under his brood pouch, a fold of feather covered skin that extends from his lower belly. After transferring the egg, the female travels back to the ocean to feed. She will be gone for about two months. To protect themselves from frigid temperatures that drop to as low as -40°C (-40°F), the left-behind males huddle together for warmth.

The female returns from her foraging trip a few days before the egg hatches. She takes over incubation duties, reliving the now very hungry and exhausted male, who has lost nearly half his body weight, to go to sea and forage. The egg usually hatches in August and the female broods the chick until the male returns. She then goes to sea again but for a shorter time, and the male and female alternate foraging trips and chick care duties.

In October at 45 to 50 days of age, the chick leaves its parents to join a group of chicks, (a crèche), that are densely packed together for warmth and protection. Adults forage and feed the chick together until it begins to molt to replace its down with the feathered waterproof plumage of a juvenile. The chick does not eat during the molting process which takes about two months. Feathered juveniles go to sea in December. At this time they are half the weight of an adult.

Behavior

The Huddle: Emperors are social, non-territorial birds and they depend on each other to survive very cold windy days by forming huddles to stay warm. Huddling cuts the heat loss by as much as 50 percent. The atmosphere inside the huddle is one of group cooperation. In a continuous circling whirlpool-like motion, each penguin takes its turns occupying the warm center spots and cold outside spots in the huddle. Penguins on the edge of the huddle move in out of the wind and cold as those in the center move toward the wind and cold, eventually reaching the edge of the huddle again. This constant movement causes the huddle to shift and in a blizzard, it may move as much as 200 meters (656 feet).

Vocalization: Unlike many other penguins, Emperors are not territorial and they do not have individual nests. Living as they do in densely crowded colonies, they rely on vocalization to find mates and chicks. Their voice system has two different frequencies. One is a shorter wave length that travels long distances and the other is a longer wave that travels shorter distances—both are important to find mates and chicks that may be somewhere among hundreds of penguins. Trumpet-like calls made with the head pointed up in what is described as the ‘Emperor Song’, are calls of ecstasy or relief. The mated pair is silent from the time they bond until the female returns from her first voyaging trip after laying the egg. In the crèches chicks use whistles or humming sounds together with head nods up and down as they beg for food.

Molting: When chicks begin to exchange their down for feathered plumage, the adults go to sea on a premolt trip to forage and restore the 50 percent of the weight they have lost during the breeding season in preparation for their energy-sapping molt. In January and February some return to their breeding site to molt: others may have to find a different location because of ice conditions. During this time the penguins do not eat and once again, lose weight. Molting is rapid in this species compared with other birds, taking only about 35 days. To help reduce heat lose, new feathers emerge from the skin after they have grown to a third of their total length, and before old feathers are lost. Before becoming fully grown, new feathers then push out the old feathers.

Adaptation

Emperor penguins have adapted over hundreds of years to be able to survive in the harsh environment in which they live. They have a thick layer of wooly down next to the skin that is covered by four layers of scale-like feathers, all coated with a waterproof substance. In addition to feathers on top of the skin, they have an insulating layer of blubber under the skin. They are able to build up extensive fat reserves and have a fat layer insulating their inner core that enables them to survive periods of extreme cold and long periods between feeding during the breeding season.

Their circulatory system of veins and arteries in their feet and flippers minimizes loss of energy used to stay warm. These penguins can actually recycle their body heat. Their blood vessels are woven together and wrap around each other so that blood flowing from the heart to the feet and flippers, and other areas close to the skin, passes next to blood flowing back to the heart, and heat is transferred from arterial blood to returning blood to minimize heat loss.

On the ice, their strong claws enable them to grip the surface of the ice as they walk. By pushing with their feet, they are either able to move forward by sliding while upright or on their belly in a tobogganing movement. Small bills and flippers conserve heat. Their nasal chambers are able to recover much of the heat normally lost during exhalation.

Longevity

About 20 years in the wild.

Conservation

Currently listed as Least Concern (Safe for Now) on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, a change in status to vulnerable is now under consideration. In November 2011 a petition was submitted to the United States government requesting that Emperor Penguins be listed as threatened or endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Emperor Penguins are the most ice-dependent of all penguins, and ice is crucial to their survival. Scientists are concerned that these penguins may not be able to adapt fast enough to the impacts of global warming on their icy Antarctic habitat. These include the rapid melting of the ice they depend on for breeding grounds and a decline in krill availability, both a food source for the penguins and also for the schooling fish that are a major part of the Emperor Penguin diet.

At sea, adult Emperors are preyed on by leopard seals and killer whales. However, because of their size, remote isolation location, and lack of introduced predators, adult Emperor Penguins are not susceptible to predation while on the ice and inland. Predation of chicks by South Polar Skuas and Southern Giant Petrels is high.

Special Notes

In late 2011 and early 2012, a team of British and U.S. scientists used high resolution pan-sharpening satellite imagery to do a census of Emperor Penguins. On the ice, the Emperor Penguins with their black and white plumage stood out against the snow and colonies were clearly visible on satellite imagery. Their study found four previously undiscovered colonies, increasing the number of known colonies from 42 to 46. The study also almost doubled the size of the Emperor population from the previously estimated 270,000-350,000 to 595,000 birds. This 2012 satellite study also revealed 235,000 breeding pairs in contrast to the 135,000-175,000 estimated in 1999. The researchers believe that the methods used in their study are a cost-effective way to provide accurate information for international conservation efforts..”

The Emperor Penguin was first described in 1844; however, it was not until 1902 during the Scott-Schaleton voyage of the Discovery that a breeding colony was discovered at Ross Island’s Cape Crozier. In spring 1903 when Discovery was trapped in ice, a biologist aboard the ship was able to study the breeding colony in detail. He thought he would see eggs, but instead, he observed well grown chicks. He correctly concluded that eggs had to be laid in the middle of the Antarctic’s winter for chicks to be at this stage of development in the spring. In late June 2011 an expedition returned to Cape Crozier in the austral winter and observed eggs, confirming the 1903 hypothesis that Emperor Penguins lay their eggs in winter, the only penguin species to do so. Ross Island is the site of the United States McMurdo Station and a census of Cape Crozier’s Emperor Penguin colony is done annually. Today there are an estimated 600+ breeding pairs. The colony, the most southern of the 40 known Emperor colonies, is still recovering from a large iceberg that blocked ocean access for the colony in 2001, devastating it.

SPECIES IN DETAIL | Print full entry

Emperor Penguin

Aptenodytes forsteri

CONSERVATION STATUS: Safe for Now

CLIMATE CHANGE: Vulnerable

The Aquarium’s Emperor Penguin is one of three models in the June Keyes Penguin Habitat that illustrate the wide size range among the world’s penguins. The Emperor is the largest of the three penguin models, (Emperor, Magellanic, and Little Blue), and this four foot model has become a very popular photographic opportunity.

Breeding: The Emperor Penguin breeds on pack ice surrounding the Antarctic continent, Antarctica Peninsula, and islands off the peninsula up to 18 km (11.2 mi) offshore. Land colonies have been seen at Dion Island on the Antarctic Peninsula and at Taylor in the Australian Antarctic Territory. Vagrants have been seen at the South Shetland Islands, Tierra del Fuego, the Falklands, South Sandwich Islands, Kerguelen Island, Heard Island, and New Zealand.

Non-breeding: Little is known about the migration patterns of Emperor Penguins, but adults seem to stay close to permanent ice while juveniles migrate as far north as the polar front (zone of transition between polar and subtropical and tropical air masses).

During breeding season, colonies are usually found inhabiting the stable fast ice attached to the ice shelves and coastlines surrounding the Antarctic continent. The most successful colonies are those that are established on stable pack ice in bays between islands that are somewhat sheltered from the fierce and harsh Antarctic winter winds by icebergs and ice cliffs. From January to March, the austral summer, they inhabit Southern Ocean waters.

Emperor Penguins, the largest of the world’s penguins, have a large head; short, thick neck; and a wedge-shaped tail. Their upper bill is black but the coloration of the lower bill varies and can be pink, orange, or lilac. Adults have the basic black and white coloration of most penguins, but they also have some distinguishing coloration in the form of a pale yellow upper breast connecting to bright yellow ear patches. The head, neck, chin, and throat are black with some white areas on the sides of the head and neck. The back is a blue-gray-black color, and the belly and undersides of the flippers are mostly white. Between November and February, the dark plumage fades from black to a brownish color. Unique to Emperors, their feet and the base of their bill are feathered, as are the outer side of their flippers. Juveniles lack the yellow plumage of adults; their ear patches, chin, and throat are white; and they have an all-black bill. Chicks have a black and white face and a body covered with silver-gray down.

Standing height: 0.9-1.2 m (3-4 ft)

Length, the measurement from tip of the beak to end of the tail): 1.1-1.3 m (3.7-4.3 ft) Weight: 22 to 45 kg (49-99 lb)

The weight of these penguins varies seasonally. They are heaviest at the start of the breeding season after spending several months foraging, and at the end of the breeding season after their pre-molt foraging. Both males and females lose weight during the breeding season when they are caring for eggs and feeding chicks.

Adult Emperor Penguins consume 2-5 kg (4.4-11 lb) of food per day except at the start of the breeding season or when they are building up their body mass in preparation for molting. Then they eat as much as six kilograms (thirteen pounds) per day.

Although the diet of Emperor Penguins varies by location and may include fish, krill, or squid, the most important food source is fish, especially Antarctic silversides. Krill and glacial and hooked squid supplement their fish diet. Foraging, which is usually done in flocks, occurs in ice free ocean waters and in tidal water in cracks in the pack ice. While some prey is captured by surface feeding, the usual method is by long, deep, pursuit diving. Emperors are very efficient divers. Shallow dives take two to four minutes while deeper dives can last as long as 12 minutes. Average dive depths are 18 to 21 m (60 to 70 ft). The tongue has rear-facing barbs to prevent prey from escaping when caught.

<

figure>

Emperor Penguins become sexually mature at three years of age; however, they usually do not start breeding until four to six years old. In late April/early May at the start of the austral winter, the march of the penguins begins when the birds exit the frigid ocean water and climb onto the pack ice. They then waddle and toboggan on their bellies at a speed of one km/hr (1.6 mph) to the breeding site, usually where they were born. There are about 46 known colonies of Emperor Penguins and the distance of the rookeries are 96 to 160 km (60-100 mi) inland.

Unlike many other penguins that usually mate for life, Emperors choose a new mate each year. They are faithful to that mate for the breeding season only. The male uses posturing and vocalization to attract a female. When he is successful, the pair waddles around the colony together. Then, just before mating actually occurs, each bows to the other by pointing its bill close to the ground.

The female lays a single egg in May or early June which she transfers to the male. Emperors do not build a nest and for the next 60 to 64 days, the male balances the egg on top of his feet, keeping it warm under his brood pouch, a fold of feather covered skin that extends from his lower belly. After transferring the egg, the female travels back to the ocean to feed. She will be gone for about two months. To protect themselves from frigid temperatures that drop to as low as -40°C (-40°F), the left-behind males huddle together for warmth.

The female returns from her foraging trip a few days before the egg hatches. She takes over incubation duties, reliving the now very hungry and exhausted male, who has lost nearly half his body weight, to go to sea and forage. The egg usually hatches in August and the female broods the chick until the male returns. She then goes to sea again but for a shorter time, and the male and female alternate foraging trips and chick care duties.

In October at 45 to 50 days of age, the chick leaves its parents to join a group of chicks, (a crèche), that are densely packed together for warmth and protection. Adults forage and feed the chick together until it begins to molt to replace its down with the feathered waterproof plumage of a juvenile. The chick does not eat during the molting process which takes about two months. Feathered juveniles go to sea in December. At this time they are half the weight of an adult.

The Huddle: Emperors are social, non-territorial birds and they depend on each other to survive very cold windy days by forming huddles to stay warm. Huddling cuts the heat loss by as much as 50 percent. The atmosphere inside the huddle is one of group cooperation. In a continuous circling whirlpool-like motion, each penguin takes its turns occupying the warm center spots and cold outside spots in the huddle. Penguins on the edge of the huddle move in out of the wind and cold as those in the center move toward the wind and cold, eventually reaching the edge of the huddle again. This constant movement causes the huddle to shift and in a blizzard, it may move as much as 200 meters (656 feet).

Vocalization: Unlike many other penguins, Emperors are not territorial and they do not have individual nests. Living as they do in densely crowded colonies, they rely on vocalization to find mates and chicks. Their voice system has two different frequencies. One is a shorter wave length that travels long distances and the other is a longer wave that travels shorter distances—both are important to find mates and chicks that may be somewhere among hundreds of penguins. Trumpet-like calls made with the head pointed up in what is described as the ‘Emperor Song’, are calls of ecstasy or relief. The mated pair is silent from the time they bond until the female returns from her first voyaging trip after laying the egg. In the crèches chicks use whistles or humming sounds together with head nods up and down as they beg for food.

Molting: When chicks begin to exchange their down for feathered plumage, the adults go to sea on a premolt trip to forage and restore the 50 percent of the weight they have lost during the breeding season in preparation for their energy-sapping molt. In January and February some return to their breeding site to molt: others may have to find a different location because of ice conditions. During this time the penguins do not eat and once again, lose weight. Molting is rapid in this species compared with other birds, taking only about 35 days. To help reduce heat lose, new feathers emerge from the skin after they have grown to a third of their total length, and before old feathers are lost. Before becoming fully grown, new feathers then push out the old feathers.

Emperor penguins have adapted over hundreds of years to be able to survive in the harsh environment in which they live. They have a thick layer of wooly down next to the skin that is covered by four layers of scale-like feathers, all coated with a waterproof substance. In addition to feathers on top of the skin, they have an insulating layer of blubber under the skin. They are able to build up extensive fat reserves and have a fat layer insulating their inner core that enables them to survive periods of extreme cold and long periods between feeding during the breeding season.

Their circulatory system of veins and arteries in their feet and flippers minimizes loss of energy used to stay warm. These penguins can actually recycle their body heat. Their blood vessels are woven together and wrap around each other so that blood flowing from the heart to the feet and flippers, and other areas close to the skin, passes next to blood flowing back to the heart, and heat is transferred from arterial blood to returning blood to minimize heat loss.

On the ice, their strong claws enable them to grip the surface of the ice as they walk. By pushing with their feet, they are either able to move forward by sliding while upright or on their belly in a tobogganing movement. Small bills and flippers conserve heat. Their nasal chambers are able to recover much of the heat normally lost during exhalation.

About 20 years in the wild.

Currently listed as Least Concern (Safe for Now) on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, a change in status to vulnerable is now under consideration. In November 2011 a petition was submitted to the United States government requesting that Emperor Penguins be listed as threatened or endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Emperor Penguins are the most ice-dependent of all penguins, and ice is crucial to their survival. Scientists are concerned that these penguins may not be able to adapt fast enough to the impacts of global warming on their icy Antarctic habitat. These include the rapid melting of the ice they depend on for breeding grounds and a decline in krill availability, both a food source for the penguins and also for the schooling fish that are a major part of the Emperor Penguin diet.

At sea, adult Emperors are preyed on by leopard seals and killer whales. However, because of their size, remote isolation location, and lack of introduced predators, adult Emperor Penguins are not susceptible to predation while on the ice and inland. Predation of chicks by South Polar Skuas and Southern Giant Petrels is high.

In late 2011 and early 2012, a team of British and U.S. scientists used high resolution pan-sharpening satellite imagery to do a census of Emperor Penguins. On the ice, the Emperor Penguins with their black and white plumage stood out against the snow and colonies were clearly visible on satellite imagery. Their study found four previously undiscovered colonies, increasing the number of known colonies from 42 to 46. The study also almost doubled the size of the Emperor population from the previously estimated 270,000-350,000 to 595,000 birds. This 2012 satellite study also revealed 235,000 breeding pairs in contrast to the 135,000-175,000 estimated in 1999. The researchers believe that the methods used in their study are a cost-effective way to provide accurate information for international conservation efforts..”

The Emperor Penguin was first described in 1844; however, it was not until 1902 during the Scott-Schaleton voyage of the Discovery that a breeding colony was discovered at Ross Island’s Cape Crozier. In spring 1903 when Discovery was trapped in ice, a biologist aboard the ship was able to study the breeding colony in detail. He thought he would see eggs, but instead, he observed well grown chicks. He correctly concluded that eggs had to be laid in the middle of the Antarctic’s winter for chicks to be at this stage of development in the spring. In late June 2011 an expedition returned to Cape Crozier in the austral winter and observed eggs, confirming the 1903 hypothesis that Emperor Penguins lay their eggs in winter, the only penguin species to do so. Ross Island is the site of the United States McMurdo Station and a census of Cape Crozier’s Emperor Penguin colony is done annually. Today there are an estimated 600+ breeding pairs. The colony, the most southern of the 40 known Emperor colonies, is still recovering from a large iceberg that blocked ocean access for the colony in 2001, devastating it.