How to Train a Sea Lion (and a Rabbit)

Hugh

Thursday, April 10, 2008

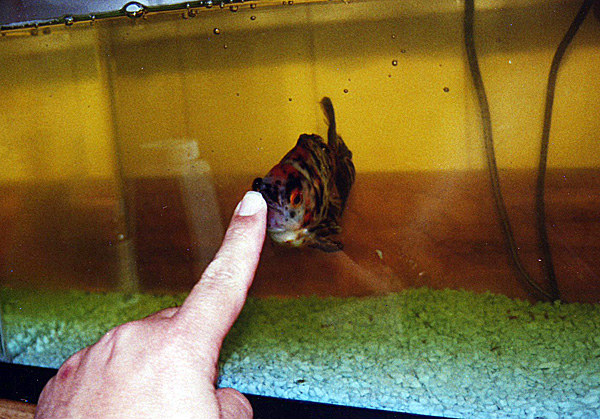

One of the questions that I hear a lot as a volunteer marine mammal trainer is how do we teach the sea otters, seals and sea lions to do all the neat behaviors that they see during a presentation and how can they get their own pets to behave so well.

Well, if I were to start talking about operant conditioning, stimulus-response, BF Skinner, discriminative stimulus, primary and secondary reinforcement, least reinforcing scenario and variable and non-variable reinforcement I usually end up getting a lot of blank stares back. So I’ve learned to put it in more personal terms.

Here in a nutshell is how to train an animal—Make it a happy experience when an animal does what you want them to do and don’t give any feedback when they don’t. Give a positive reaction for a behavior done correctly and don’t give any reaction (sort of a mini time-out) when they behave incorrectly. In marine mammal training we call it using positive reinforcement.

For many animals its food that makes them happy. For instance, our sea otters are very food motivated. They will do just about anything to get their tasty clam reward. So when they do a behavior correctly like placing their paw on a target pole when asked, they receive a clam as a reward. It reinforces the desired behavior. However for some animals, other things like a pat on the head or a favorite toy may be used as a reward. I once knew a bomb sniffing dog whose favorite reward for finding explosive material was to be allowed to play with her favorite rubber ducky. Yes a rubber ducky! Even the fun of the training session itself can be a reward for the animal. Parker the sea lion is a prime example of this. He loves to work with his trainers even when he’s not hungry.

Sometimes it may be awkward or impossible to get the reward to an animal exactly when they do the behavior you want (it would be difficult to toss a fish to a sea lion that’s in the middle of a back flip), so you have to have some way of bridging the time between when the correct behavior was done and when the reward is given. With our marine mammals we can use a whistle as a bridge to let the animal know that it has done something correctly and that their reward will follow. We teach this bridge early in their training by blowing the whistle whenever we hand a fish to the animal. They soon associate the whistle with the food (think Pavlov’s dogs) and react positively when they hear it. They’ve learned that when they hear a whistle that they have done something correctly and that a reward will follow. The timing of the bridge is also important. If you are training Parker the sea lion to leap high out of the water you want to blow your whistle when the jump is highest. If you give the bridge while Parker is still going up, he will interpret the correct behavior as just the leap itself. If you give the bridge when he is on his way down, he will think that the fall is what you want. By bridging at the top of the leap, you let him know that the height of the jump is the behavior you want (we call this the criteria of the behavior).

An important thing to keep in mind when you are training an animals is that you don’t want to make the training session itself frustrating for the animal so it best to take baby steps with the critter you are training and break down the behavior you want to teach down into smaller behaviors that can more easily be rewarded. Keep the sessions positive. The first baby step I used in training our blind seal Ellie to retrieve a ball was actually having her touch the ball or ring held in my hand that I splashed next to her. From there I used baby steps to train her to find and push the objects back to me and then gradually increased the distance of the retrievals. Each small success could be rewarded and built on each other. You should also make sure that the hand and voice signals you give the animal to perform the behavior are consistent from session to session so as not to confuse the animal about what you are asking for. Never set up an animal for failure by making a step too hard or confusing thus frustrating the animal and always try to end a training session on a positive note like asking for a simple behavior that an animal can do easily for a reward.

Another training consideration that you also want to make sure of is that the actions and environment surrounding the behavior being trained are neutral or positive experiences. For example, you don’t want to teach a dog how to walk on a leash by suddenly snapping the leash on the dog and pulling the confused animal along a busy street filled with scary cars and trucks. If you did you just associated the leash itself with an unpleasant experience. You first want to introduce the leash gradually and as part of a pleasant experience like feeding or play time or perhaps a pat on the head.

To give an example, I once taught a rabbit to walk on a leash out in public. Wanting to take our pet rabbit Buster with us on a road trip to my wife’s home town in Kansas, I decided to train the bunny to walk on a leash using the training skills I had acquired working with the Aquarium of the Pacific’s seals and sea lions. That way Buster didn’t have to stay in her kennel all the way to Wellington. She could stretch her paws when we stopped to stretch our legs. First I had to figure out what I could use as a reward for Buster doing what I wanted. Buster was not a food motivated animal. What she did enjoy was a rub on her head so I used that as her reinforcement. To bridge the gap between when she did something I wanted and Buster getting her head rubbed, I used the word “Good” as a bridge. I would say “Good” every time I would rub her head. She soon associated the word with the positive experience of her head being rubbed. I then broke down the behavior I wanted to train into smaller steps. I first placed the harness that I eventually wanted to strap on Buster nearby on the ground during the times that I would give her a rub on her head. Later I would lay the harness on her for short periods, all the while reinforcing her calmness around the harness. Eventually she got used to me actually strapping the harness on her for extended period. Only when she was completely use to the harness did I actually attach the leash to it. From there we went back to baby steps which eventually led to her gradual introduction to walking with me while on the leash-first in a quiet public park and then later on a busy bike path at the beach where I reinforced her calmness around people and bikes.

While knowing the steps to train an animal is important, it’s just as important to have a bit of knowledge about the animal’s Natural History. In my bunny scenario&mdashA hare like a jackrabbit has the first instincts to quickly hop away from a threat. A rabbit like Buster who was part brush rabbit and part domesticated rabbit; however, has a different threat response than its cousin the hare. Rabbits will actually huddle still under brushes and other objects to hide when a threat is near, using their jumping abilities to escape only as a last resort. Thus I knew that when Buster got real nervous she would huddle around my legs and I could respond by reassuring her and calming her down. If I didn’t know this fact about rabbits, I might not have taken notice of her nervousness and she could have tried to bolt away from her perceived threat while on the leash and injured herself.

How long did it take to train a rabbit to calmly walk on a leash? Unlike sea lions, rabbits have a very short attention span so I only trained her in short 5 minute sessions once or twice a day depending on my schedule. All in all it took about 10 weeks from introduction of the harness to confidently walking out in public. One of our practice walks involved a humorous story. I was walking Buster on her leash along the beach when an upset looking lifeguard came toward us while angrily pointing at a sign on a post. When he got closer he did a double take and then started to laugh. What had happened was when he saw me with an animal on a leash he assumed it was a small dog and was pointing to the NO DOGS ALLOWED ON BEACH sign. I guess because the sign didn’t say anything about rabbits, he allowed us to continue our beach walk. When Buster finally made her trip to Kansas she was a well trained animal companion.

Just because you don’t have a handy sea lion around doesn’t mean that you can’t have fun training animals. Any critter can be trained as long as you know what makes it happy!